KATHERINE CLARK IS TAKING ON THE TROLLS

The most prominent advocate for targets of online abuse is becoming one herself, and refusing to let it stop her.

When Katharine Clark was a state senator in 2012, a man posted on her Facebook page, "People like you deserve to get shot."

Clark had been a prosecutor and had served on the local school board. She was no stranger to public antagonism. In 2010, a local comedian had done a stand-up bit in which he'd called her a whore. But this was the first time in her political career that she had been truly scared. "As much as people always say you have to have a thick skin to run for office, you never really can ignore it," she told me in May when I visited her at her home in Melrose, a suburb north of Boston.

Clark's living room is decorated with books and family photos and a cross-stitched pillow that reads "A Woman's Place is in the White House." (You know which presidential candidate she's supporting.) It's quiet in here today—her three teenage sons are at school, and her husband Rodney is at work. Bodie, the dog, wanders in and out of the living room. Clark, who has kind blue eyes and a layered gray bob, is wearing a cerulean suit jacket and beaded necklace that are distinctly "politician."

The fact that Clark is a politician means that police were quick to respond when she reported the threatening Facebook comment to the state police, who found the man who'd posted it and warned him not to do it again.

Her story is the exception, though. For almost everyone else who endures online insults and threats, justice is much harder to come by. Sometimes the harassers are protected by anonymity: It's pretty much impossible to pursue an attacker when you don't know who the attacker really is. Even when the harasser's identity is known, it's difficult for victims to find police who take the behavior seriously enough to shut it down. It's a vicious cycle that's hard to break, because when someone speaks up, they often become a target themselves.

Clark has been at the forefront of the push to reform the way that we handle online harassment, becoming perhaps the most outspoken member of Congress when it comes to the obstacles that women are facing online. She's introduced two different pieces of federal legislation, spoken at tech conferences, reached out to victims, worked to educate police, and directly lobbied social-media companies to change their policies.

And for her efforts, she's become even more of a target of the very abuse she's attempting to combat.

In 2014, several female video-game designers and writers spoke up about sexism in the industry and were met with brutal online attacks as a result. (You might have heard of this ongoing problem, which is known by the short-hand Gamergate.) They were inundated with hateful emails, tweets, and comments. Many were doxxed, which is when private information, such as your home address and phone number, is made public online. This, in turn, meant they were forced to leave their homes or offices, driven by the fear that they were now in physical danger as well.

Clark's staff realized that one of the women who was being harassed, a game designer named Brianna Wu, lived in her district. The congresswoman contacted Wu, and Wu told her that she had received more than 100 death threats, yet she wasn't getting support from local police. The FBI wasn't being particularly helpful either.

Clark's office called the FBI on Wu's behalf. "They were pretty clear with us that it wasn't a matter of resources. It just wasn't a priority," Clark recalls. "We decided that we would try and make it a priority for them." Soon after, she and her team began working on legislation to educate police about the problem of online harassment. "In a political environment where law enforcement has frankly not been very helpful for my family at all, Katherine Clark is the reason we're getting any attention on this at all," Wu told WBUR News last year.

For Clark, the inadequate police response was indicative of something much bigger. "This is more than annoying comments," she says. "This really interferes with how women make a living, and how they are succeeding or not succeeding professionally." She explains that many careers require women to participate publicly in social media. Other lucrative professions, like software engineering, are primarily digital, so maintaining an online presence is not optional. When the distinct possibility of online harassment deters women from making certain career choices, Clark says, this is about more than personal safety. It's an economic issue with immediate financial consequences. "For a lot of victims of online abuse, it ends up being lost earnings for court dates," Clark explains. "It's hiring security online to try to make that information private. It's hiring attorneys. It becomes a real expense and a burden, and we have to do a better job."

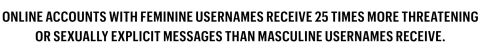

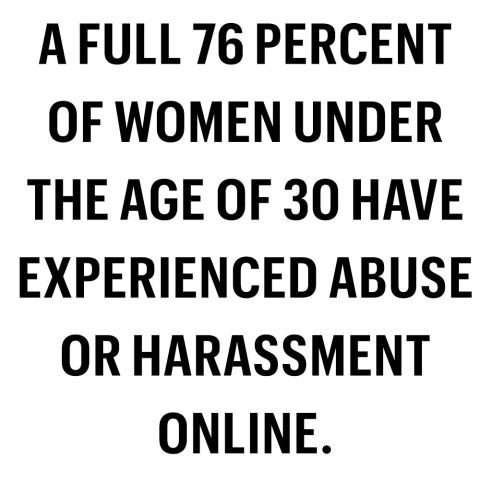

Of course, men are the recipients of online harassment, too, but study after study confirms that threats and hate speech are disproportionately targeted at marginalized groups like women and people of color. According to research by the University of Maryland in 2006, online accounts with feminine usernames receive 25 times more threatening or sexually explicit messages than masculine usernames receive. More recently, the Guardian analyzed 70 million comments, and found that, of the ten most abused writers on its site, eight are women and two are black men. And an Australian study found that a full 76 percent of women under the age of 30 have experienced abuse or harassment online.

In November of last year, Clark introduced the Internet Swatting Hoax Act, federal legislation to address harassment that originates online. When a person is "swatted," anonymous harassers call the local police to falsely report a violent incident at the target's address, ensuring that heavily armed cops and, often, entire SWAT teams storm the target's house in a misguided attempt to help.

Although swatting might not seem like online harassment—police banging on the front door are very real, not virtual—it's a type of intimidation that often comes as a result of doxxing. And it's an increasingly common way that online threats translate to real physical risk for women who are targeted. (Swatting can also be disconnected from online harassment. Clark is aware of some victims who were targeted at random, like an elderly couple in her district.)

Federal laws prohibit bomb threats and hoax terrorist attacks, but they do not apply to false reports of other emergency situations. In other words, there's a swatting loophole. Clark's legislation would close it by making swatting a federal crime, and punishing perpetrators according to the amount of harm they inflict on their victims. Some swatting incidents "are basically very dangerous prank calls," Clark says, "and some of them are very well-thought-out tools to harass people, to try and hurt them, to get the police to injure them."

It was 10 p.m. on a Sunday, three months after she introduced the swatting bill, and Clark had just gotten home after an event. Her sons were in their rooms, and she and Rodney were settling in to watch an episode of VEEP. That's when she noticed the flashing lights. Cop cars were blocking off either end of her street. She ventured outside, where she realized that the officers were facing her house. And they were carrying long guns that looked like rifles. Two officers approached her and told her that they'd received an anonymous report—from a computerized voice—that there was an active shooter at her home.

Active shooter. Computerized voice. Clark put the pieces together: "The minute they said 'We received an anonymous call,' I'm like, "Oh, I know what this is.'"

The police were quick to believe her when she explained that it was a hoax. But Clark realizes that, like their swift response to the threatening Facebook comment a few years ago, the police treat her differently because she is a politician. In other swatting situations, there have been instances in which the victims have almost been shot or injured.

Although the people who swatted her were never identified, Clark suspects that she was targeted because of the legislation. She understands that this is one of the consequences of fighting anonymous, online abuse. Most internet harassers would not come to her doorstep with a gun themselves, but many are willing to use a computerized voice to ensure the police show up with their weapons drawn. Anonymity lowers the stakes for the harasser—but not for the victim.

Yet Clark has not allowed this to deter her. This spring she appeared at SXSW, where she announced a new bill to ensure that police departments are properly trained to address online harassment and threats. "I think that police officers want to help," she says, but "they just don't have training. We need everybody to be able to know how to do a basic forensic investigation online." In other words, victims need to know how to keep track of the harassment they receive, from emails to comments to tweets. And police need to know how to make sense of it all. That's why the bill would also create a national resource center for online crimes.

Clark has also been trying to work with social-media platforms like Twitter and Facebook and Reddit to ensure they're addressing these issues from the inside. Her office recently found success with this approach: They sent a letter to Genius, a social site that allows any web page to be annotated and commented on, explaining how its software could be used as a harassment tool. In response, Genius added a "report abuse" button. For her efforts, Clark was also rewarded with a fresh wave of nasty tweets from her detractors, politely suggesting she "go drink bleach" and calling her a four-letter word that starts with "c."

Both bills that Clark has introduced are stalled, stuck in the infamous congressional gridlock. Her staff thinks the swatting bill still has a fighting chance. They are more pessimistic about the odds of passing the law enforcement training bill, which has a $20 million price tag.

But there is at least one successful precedent for Clark's effort to change things. The legislation she's proposed is similar to the Violence Against Women Act, which since 1994 has funded training for cops and courts in how to address intimate abuse and stalking. Clark sees other parallels between the two issues: Online harassment is written off as unsolvable by some and inconsequential by others, which is similar to how domestic violence was once seen. "Why don't you just leave him?"—once the standard dismissive response to victims of abuse—is akin to "Why don't you just close your computer?" Just as police were once completely unequipped to respond to domestic violence calls, today many departments struggle to help people who report online harassment. When, for example, journalist Amanda Hess reported online rape threats she'd received, a local police officer responded to her, "What is Twitter?" "It sort of compounds the harm that was done when nobody understands what you're going through," Clark says.

Today most people recognize domestic violence as a crime with horrible consequences for women. Perhaps in the future online harassment and threats will be viewed the same way. "We're not going to be able to prevent it all," Clark says, "but there has to be resources and training that gives people a reasonable level of protection and safety." And, she adds, she's going to keep working until we get there.

Read more of Ann Friedman's work here.

Permalink: https://katherineclark.house.gov/2016/7/elle